Hello! I’m Jesse Carpenter

My passion for computers started back in the mid‑1970s at the University of New Mexico (UNM). Out of curiosity (and maybe just wanting to see what all the fuss was about), I took a business class to learn COBOL, a mainframe programming language. I still remember the ritual of keypunching code onto cards and waiting for the results from those noisy line printers. It was slow, but I actually kind of enjoyed the challenge—and even the waiting taught me patience and a deeper appreciation for programming.

Fast forward to the mid‑1980s, when I stumbled across a Macintosh Plus at the SDSU campus bookstore. I was hooked! The graphical interface was a game‑changer, and before I knew it, half an hour had flown by as I poked around. After moving to San Jose with my wife (who was in the Navy), I bought my own Macintosh Plus, a whopping 20K external drive, the Mac printer and more. I loved how it made editing papers so much easier. From there, it was one upgrade after another: the Mac II, the Bondi Blue iMac G3, and eventually the Mac Pro. I always tried to keep up with the latest and greatest tech, and every new machine felt like starting a fresh adventure.

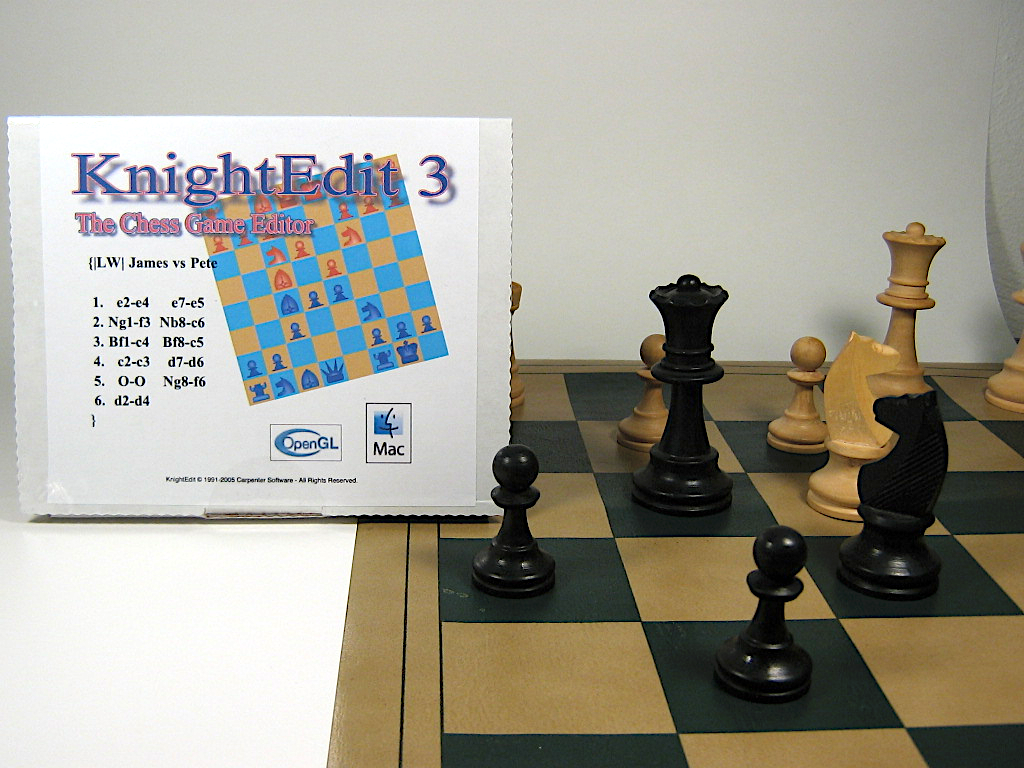

Somewhere before 1991, I got the idea to program a chess game editor for the Mac. I was always looking for new things to try, and this seemed like a fun challenge. If you remember America Online (AOL), you might recall the classic “You’ve Got Mail” sound—back then, I thought it’d be cool to email chess moves to a friend. The graphics were simple pixel chess pieces on a two‑dimensional board, and I even got to play around with Apple’s TextEdit source code and my favorite tool, ResEdit (the one with the Jack‑in‑the‑Box icon). Every project was a new adventure, and I loved every minute of tinkering and learning.

AOL Mail eventually became a free webmail service, enabling wider access. KnightEdit gained popularity among Macintosh users, which prompted me to hire someone for advertising.

Apple’s programming languages evolved from BASIC and Pascal to C, C++, Objective‑C, and, most recently, Swift. I wrote all my code in Pascal at first. Apple created a "Pascal to C" converter (p2c) for developers navigating major language changes. In 1991, I transitioned to C++, and object‑oriented programming was entirely new to me, and learning it was a challenge. When Objective‑C arrived, I struggled further with OOP concepts. The pace of technological advancement just keeps accelerating.

After moving back to Albuquerque, I started Carpenter Software and launched KnightEdit.com. I was always curious about new programming languages, so I took some junior college classes in C++ to get the hang of object‑oriented programming. After that, I started exploring 3D game programming with engines like WildMagic and Torque. Computer graphics quickly became my new obsession, and I loved seeing what I could build next.

Games incorporate artificial intelligence—not always academically, but in practical, engaging ways. Game agents could act intelligently, like an orc chasing a player’s avatar. As the field grew, the demand for smarter, more immersive gameplay led to widespread exploration of topics such as pathfinding, decision‑making algorithms, and adaptive enemy behavior. Suddenly, hundreds of books on Game AI appeared, and online communities flourished, sharing new approaches and techniques. This period marked an explosion in creativity, as developers pushed the boundaries of what AI could achieve within the constraints of home computers.

My curiosity about game AI soon led me to robotics. The idea of bringing digital logic into the physical world was thrilling. I started with simple robotic projects—like building a robot controlled by a thumb joystick and experimenting with basic sensors. Exploring this field, I discovered the Arduino Uno—unique for its removable Atmega328p chip. With so many microcontrollers available, I chose the Arduino Uno for its flexibility, community support, and approachable learning curve.

Whenever I’m working on robotics software, I like to use a simulation to see how the robot behaves. Take the Unity Game Engine, for example—I made a "Joystick Algorithm Simulation" (there’s a video on YouTube if you want to check it out). Watching the robot respond as the joystick moves it around is honestly a lot of fun. I tend to tweak things until it feels just right. There’s something really satisfying about seeing all the pieces come together and work the way you imagined.

I learned some electronics while helping my father in his TV repair shop—the kind filled with tubes, not transistors. Those early hands‑on experiences taught me the basics of troubleshooting and circuit design, even though technology has changed dramatically since then. With the Arduino Uno, I dove into books and taught myself everything from circuits to digital programming, enjoying the process of bringing small inventions to life. The Arduino IDE uses C/C++, and I soon created a GitHub account called MageMCU to share my projects and collaborate with others.

During this time, I also developed my own website technology, writing code for both the KnightEdit and Carpenter Software sites using HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. Web development opened up a new realm of creativity for me—designing interfaces, optimizing user experiences, and learning how to make my applications accessible to a broader audience. Each website became a living project that evolved alongside my skills and interests.

Now, even at 70‑plus, I’m still amazed by all the new tools out there—Google Drive, Firebase, Gemini, and even AI assistants like Grammarly. They make it easier (and a lot more fun) to experiment and learn new things. My love for programming hasn’t gone anywhere, and I’m always excited to try out the latest gadgets and software. Like my dad used to say, “I tell you“ ‑ there’s no stopping me. Or, as Paul put it: “…not until I drink from the silver spoon.”